Trade Dress Revival Could Lead to Exclusion Order Under Section 337

November 6, 2018

By: Susan G. L. Glovsky and Patrick A. Quinlan

Trade Dress Revival Could Lead to Exclusion Order Under Section 337

Federal Circuit Takes an Opportunity to Correct “Series of Errors” by ITC

- Owners investigating enforcement of trademarks against articles that are being imported should consider the availability of an exclusion order from the ITC

- Trademark rights enforceable at the ITC can arise from common law or from a federal registration

- Federal Circuit offers guidance on secondary meaning and other important trademark issues

Under Section 337 of the Tariff Act, the International Trade Commission (ITC) “shall direct” that articles it determines violate Section 337 be excluded from entry into the United States. Importation into the United States of articles that infringe a valid and enforceable trademark or patent claim are examples of violations that can form the basis for an exclusion order. The ITC handles far more complaints for violation of Section 337 based on allegations of patent infringement than allegations of trademark infringement.

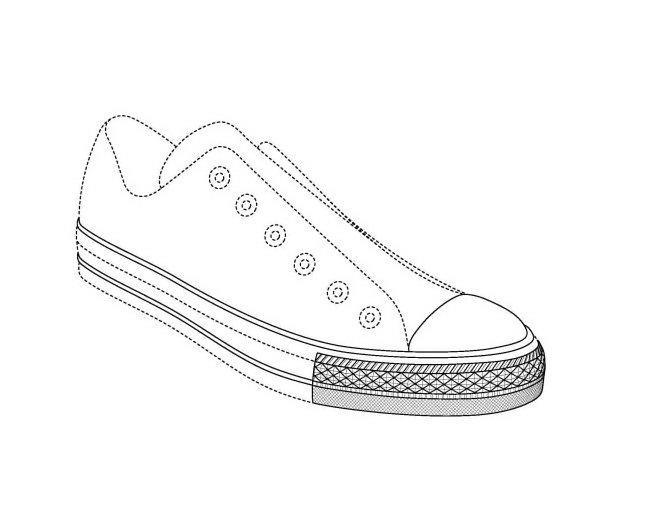

In Converse v. ITC and Sketchers, New Balance, et al. (Fed. Cir. 2018), the case began with Converse, Inc. bringing a complaint with the ITC to enforce its Chuck Taylor trade dress depicted in the following mark:

The ITC denied the exclusion order, finding the registered mark invalid and that Converse could not establish the existence of common law trademark rights.

In its decision vacating and remanding to the ITC, the Federal Circuit took the opportunity to address a “series of errors” by the ITC that required remand to the ITC. The decision is of interest beyond ITC proceedings as the issues addressed arise in trademark prosecution and proceedings at the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board and in district court proceedings.

The Federal Circuit began its analysis with a statement that there is a single mark to which different rights attach from the common law and from federal registration. In doing so, the Federal Circuit rejected reference to a concept of two separate marks – a registered mark and a common law mark – as confusing and inaccurate. The type of mark at issue is a product-design trade dress, which, like color, is not inherently distinctive. To register or enforce a mark that is not inherently distinctive, the owner must show that the mark has acquired distinctiveness, or “secondary meaning”; that is, the owner must prove that the mark has become distinctive as applied to the goods or services in commerce.

Relevant Date for Determining Secondary Meaning

Timing for establishing secondary meaning is the focus of the first error identified by the Federal Circuit. The ITC failed to distinguish between alleged infringers who began infringing before Converse obtained its trademark registration and those who began afterward, and the ITC never determined the relevant date for assessing the existence of secondary meaning. The ITC did characterize 2003 as the “date of first infringement,” but proceeded to cite evidence after that date. The Federal Circuit further found:

- “In any infringement action, the party asserting trade-dress protection must establish that its mark had acquired secondary meaning before the first infringing use by each alleged infringer.”

- The secondary meaning analysis primarily seeks to determine what is in the minds of consumers as of the relevant date. The most relevant evidence will be the trademark owner’s and third parties’ use in the recent period before first use or infringement. Uses older than five years before the relevant date should only be considered relevant if there is evidence that such uses were likely to have impacted consumers’ perceptions of the mark as of the relevant date; in contrast, when an alleged infringer challenges the present validity of a trademark registration, validity depends on whether the mark had acquired secondary meaning as of the date of registration.

- For infringement in the period after registration, the Lanham Act entitles the owner of the registered mark to a presumption that the mark is valid, including that it has acquired secondary meaning; the presumption that the mark is valid shifts both the burden of persuasion and the initial burden of production to the challenger to rebut the presumption.

- The presumption of validity afforded to registered marks does not apply to infringement that began before registration; the registration and its accompanying presumption of secondary meaning operate only prospectively from the date of registration.

- For each respondent whose first use came before Converse’s registration, Converse must establish, without the benefit of the presumption, that its mark had acquired secondary meaning before the first infringing use by that respondent.

Factors to Be Weighed Together to Determine Secondary Meaning

The Federal Circuit further clarified this area of the law by adopting the following six factors to be weighed together in determining the existence of secondary meaning:

(1) association of the trade dress with a particular source by actual purchasers (typically measured by customer surveys); (2) length, degree, and exclusivity of use; (3) amount and manner of advertising; (4) amount of sales and number of customers; (5) intentional copying; and (6) unsolicited media coverage of the product embodying the mark.

The Federal Circuit agreed with the ITC that evidence of the use of similar but not identical trade dress may inform the secondary-meaning analysis, but such uses must be substantially similar to the asserted mark and, on remand the ITC must constrain its analysis of both Converse’s use and the use by its competitors to marks substantially similar to Converse’s registered mark.

The ITC is to give little probative weight to the only survey that survived the ITC for the appeal (eight were rejected by the administrative law judge) for purposes of infringement, unless the survey was within five years of the first infringement by an intervenor in the case. If secondary meaning at the time of the registration remains an issue on remand, the survey may have relevance because it was conducted within two years of the registration. The Federal Circuit opinion did not resolve and leaves to the ITC conclusions to be drawn from the survey concerning secondary meaning.

Accused Products That Are Not Substantially Similar Cannot Infringe Trade Dress

The Federal Circuit provided further guidance on the likelihood of confusion analysis for determining infringement. “In the context of trade-dress infringement, we also hold that accused products that are not substantially similar cannot infringe.” The ITC on remand “should reassess the accused products to determine whether they are substantially similar to the mark in the infringement analysis.”