Long-Anticipated Supreme Court Ruling in Warhol Copyright Case Underwhelms

May 19, 2023

Andy Warhol, even posthumously, has a talent for attracting attention. That was true for the copyright litigation by the Andy Warhol Foundation (“AWF”) against the photographer Lynn Goldsmith concerning Goldsmith’s photo of the musician Prince. The case attracted the attention of many legal and art commentators who offered a host of different views. Most seemed to expect the Supreme Court’s opinion to signal a significant change in the transformative use test embedded in the Fair Use defense to copyright infringement. That change in the law did not occur. As the Court itself explained, its decision does not break new ground but “is consistent with longstanding principles of fair use.”

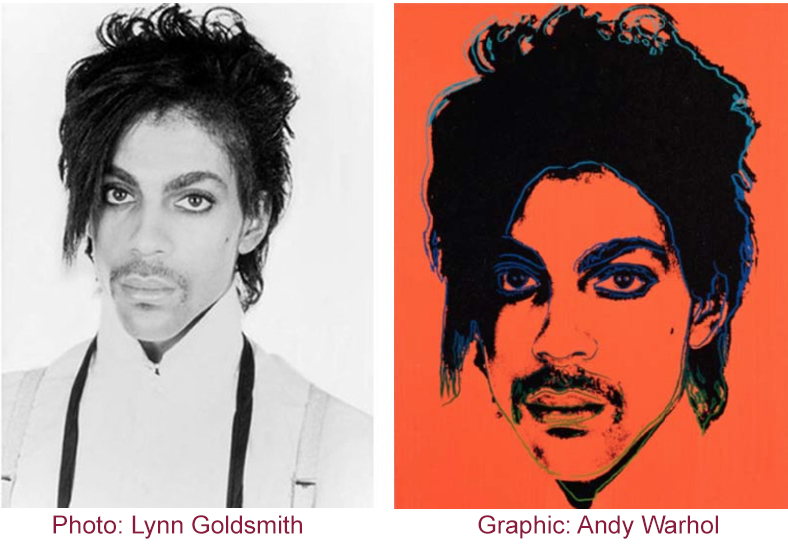

In the early 1980s, Goldsmith took a series of photos of the musician Prince and allowed the artist Andy Warhol to use a single photo of Prince “one time” as a subject reference for a piece of art. Warhol used the Prince photo to create a silkscreen “Purple” version of the Prince photo. The Warhol Purple version was published in 1984 on the cover of Vanity Fair magazine relating to a feature piece about Prince. Contrary to the “one time” use limitation, Warhol made fifteen other silkscreen versions of the photo. Goldsmith first learned of the additional Warhol works in 2016 when another silkscreened version of her Prince photo – the “Orange” version - appeared on the cover of another Vanity Fair publication paying tribute to Prince. The geometric dimensions of Prince in the Orange silkscreen were virtually identical to the dimensions of Prince in the original photo. The coloring and tone of the silkscreen versions were different from the photo. AWF claims the meaning and message of the photo and the silkscreen versions differed substantially.

Goldsmith notified AWF that the Orange version violated her copyright in the Prince photo. AWF brought a declaratory judgment action to bring the issue before a court. AWF claimed the Orange version was permitted fair use as it had a different look than the photo and had a different message – it was a comment on the barren nature of celebrity, not a celebration of Prince. The lower court found for AWF even though the use was commercial in nature (AWF, but not Goldsmith, received royalty income for the publication of the Orange version). The Second Circuit reversed, finding the Orange version was not a transformative use of the photo. The Supreme Court agreed to review the case and affirmed the Second Circuit’s ruling.

The Supreme Court ruled that because the published Orange version was a commercial use and the purpose of both the Prince photo and the Orange version were the same (portraits of Prince), the “transformative use” portion of the Fair Use Doctrine (17 U. S. C. §107) did not apply to AWF. The Court added that simply purporting to convey a new meaning or message, which almost every author of a secondary work can claim, “alone is not enough . . . to favor fair use.” Still, the Court acknowledged that Warhol may have had a different message but noted that difference was not weighty enough to favor fair use. “Even if such commentary is perceptible on the cover of [the publication], . . . the asserted commentary . . . has no critical bearing on Goldsmith’s photograph,” such as through parody or criticism. Thus, a claim of a new message or meaning in the secondary work that is unconnected to the original image “diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish)” in weight under the Fair Use analysis when the commercial nature of the use “loom[s] larger.”

The Court summarized its ruling as follows:

Lynn Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists. Such protection includes the right to prepare derivative works that transform the original. The use of a copyrighted work may nevertheless be fair if, among other things, the use has a purpose and character that is sufficiently distinct from the original. In this case, however, Goldsmith’s original photograph of Prince, and AWF’s copying use of that photograph in an image licensed to a special edition magazine devoted to Prince, share substantially the same purpose, and the use is of a commercial nature. AWF has offered no other persuasive justification for its unauthorized use of the photograph. Therefore, the “purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes,” §107(1), weighs in Goldsmith’s favor.

The Supreme Court’s ruling can be seen as limiting the scope of the transformative use prong of the fair use defense and reigning in some of the excessive uses of the doctrine. The decision will benefit photographers who often provide source material to other artists. However, it should not presently be seen in simple terms as either pro- or anti- fine art. It will take many years of lower court litigation to understand if this ruling struck the right balance for the Fair Use defense to Copyright infringement.