9th Circ. Should Overturn The Miles Davis Tattoo Ruling

February 15, 2024

Law 360

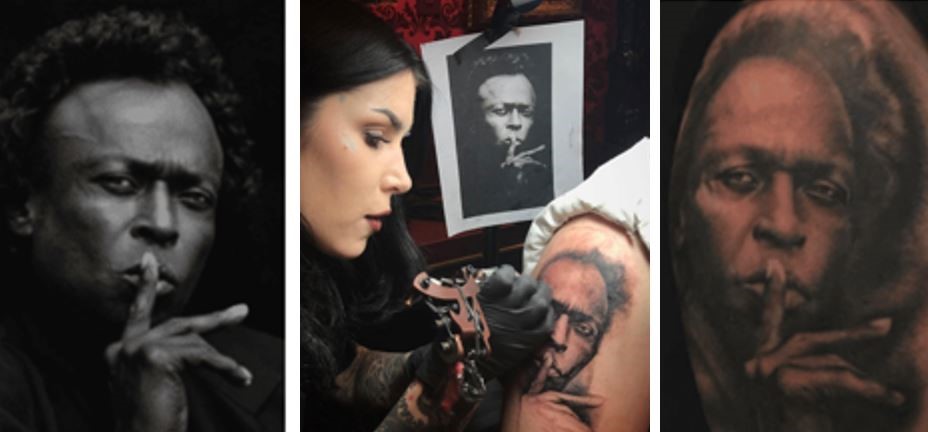

The jury in the recent Sedlik v. Von Drachenberg case decided that a tattoo of jazz trumpeter Miles Davis inked by celebrity artist Kat Von D was not substantially similar to a copyrighted photo of Davis taken by professional photographer Jeffrey Sedlik. Thus, it was determined that the tattoo did not infringe Sedlik's copyright.

The jury's Jan. 26 verdict in the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California stated only that Von D's tattoo was not substantially similar to the copyrighted image, even though Von D, whose real name is Katherine Von Drachenberg, admitted she copied the photo with tracing paper and used it as a reference photo to create the tattoo.

Defendants and others have proclaimed this case as a victory for all tattoo artists who copy the work of photographers, but that enthusiasm would likely dampen after an appeal.

Upon the anticipated appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit should overturn the ruling. The district court made a number of missteps in the case, including ineffective and confusing jury instructions, and ignoring the U.S. Supreme Court's recent guidance in the Warhol case as to the proper role of the trial court in copyright cases.

The Miles Davis Photo and Tattoo

Here, Von D specifically sought to ink a tattoo of Sedlik's Miles Davis photo on her client's arm as requested. Sedlik's photo was taken in 1989 and was the result of a three-day photo shoot. It was copyrighted in 1994. Sedlik experimented with a plethora of poses, lightings and other artistic choices before settling on the image in question.

To transform the Sedlik image into a tattoo, Von D used tracing paper and a lightbox to exactly copy the significant features of the photo. Next, she made a thermal transfer to affix the traced image to her client's arm. She used Sedlik's photo as a "reference photo" to guide her work.

A photograph contains many features that are protectable by copyright based on the original creative work of the author and other more factual features that are not protected by copyright.

A portrait photo, for example, contains plain factual material (the size and shape of someone's nose) and also contains creative features that result from the artistic choices of the photographer such as the pose of the subject, point of view, lighting and shadows, as well as the interrelation of various elements.

The prominent features of the Sedlik photo are:

- The foreground dominated by Davis' long spindly "trumpet" fingers with the index finger touching his lips to say "shush" and his other fingers, cascading downwardly;

- The index finger's distinctive fingernail and positioning slightly off center on Davis' lips;

- A low light source coming from above the subject to "paint with light" portions of the cheeks, fingers and forehead — but not the chin, the furrowed brow or cheek area near the ears;

- Davis' eyes at camera level and his gaze looking slightly left; and

- A slight halolike white glow on the left side of Davis' forehead where it meets his hairline.

Substantial Similarity Tests

To prove infringement, the copyright owner must show that the alleged infringer copied the owner's work and appropriated artistic, or protectable, elements of the photo.

The comparing party — court or jury — must determine if the creative elements of the original are found in the copy. This is known as the extrinsic test.

The comparer then looks at the overall impression of the original versus the copy. This is the intrinsic test. In each case, the comparer is looking to see if the original and the copy are "substantially similar."

The presence of the original artistic elements in the second work shows the author of the second work did not exercise her own creativity but misappropriated the creativity of the original author. Copyright law is principally intended to stop the theft of creative works.

A study of the images shows that artistic features found in the original photo are found in Von D's tattoo. This is solid evidence of infringement of Sedlik's creative work.

Note, for example, in Sedlik's image there is a thin "halolike" white line on the left side of the forehead where it meets the hair that is present in the copy. There was no need to copy the peculiar fingernails and the distended, spindly trumpet fingers exactly, as she did. Nor did she need to directly copy the off-center finger on Davis' lip, saying, in substance, "sshhh."

The legal copyright test for "substantial similarity" is notoriously hard to implement, and has been called meaningless by some commenters and a standard that can invite juror personal bias into decision-making.

To make the copyright test more meaningful and accessible to a jury, the court needs to give detailed instructions. In Jury Instruction Comment 17.19 of its Manual of Modern Civil Jury Instructions, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit strongly suggests that "the court and counsel specifically craft instructions on substantial similarity based on the particular work(s) at issue, the copyright in question, and the evidence developed at trial."

Here, the court did not heed this suggestion and instead provided the jury with only barebones instructions.

The court also rejected instructions proposed by the plaintiff. For example, the plaintiff sought an instruction that did not require proof of exact copying by the defendant and an instruction that the copyright test was to look to the substantial similarity of protected expression in the whole work, not of each and every creative element.

The court rejected the plaintiff's proposal, and instead told the jury:

It is the plaintiff's burden to identify the particular combination, selection, or arrangement of elements in his photograph that he claims is protected by copyright law. He must show that each of the accused infringements is substantially similar to this particular combination, selection, or arrangement.

The Undecipherable Verdict

The jury's verdict states that the tattoo is "not substantially similar" to Sedlik's photo. It does not state whether that conclusion was reached with respect to the extrinsic or intrinsic tests, and does not specify if it is based on only one of several artistic elements not being similar, or many elements.

The verdict does not indicate what standard the jury used. It does not hint at whether the verdict was based on the jury instructions only or instead may have been the improper product of undue deference to California's celebrity culture.

This verdict makes the jury's work effectively unreviewable by the appeals court.

The verdict form would have been improved if counsel had succeeded in having the court list on the form some of the specific protected elements the jury was to consider. Instead, the court apparently left it to the plaintiff during closing argument to identify protected elements.

Obvious Copying and a Directed Verdict

The court's insistence on having the jury decide all issues of infringement is contrary to the recent Supreme Court ruling in the Warhol case. There, the court and not the jury decided the issue of copyright infringement as a matter of law where there was evidence of direct copying.

In the Von D case, prior to the Supreme Court's decision in Warhol, the plaintiff sought a ruling from the court that merely looking at the tattoo left no doubt that Von D had copied Sedlik's photograph.

The court denied the motion because Sedlik failed to "articulate the nature of the similarities" other than to say "that there were some."

Sedlik also offered a conclusion that "the two works are so remarkably similar [to] an ordinary observer." The court, perhaps concerned about compromising its judicial role as a neutral party, was unwilling to fill in obvious details that the plaintiff did not articulate — as discussed above — about the case.

The Supreme Court Warhol Copyright Case

In Warhol, the artist Andy Warhol used a copyrighted photo of the famous musician Prince as a basis for a series of silk screen reproductions of the photo. Warhol did not have permission from the photographer Lynn Goldsmith to use her work.

The lower court in the Warhol case did not consider the issue of infringement under the substantial similarity test. Instead, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit made that decision.

The Second Circuit observed that:

[G]iven the degree to which Goldsmith's work remains recognizable within Warhol's, there can be no reasonable debate that the works are substantially similar. As we have noted above, Prince, like other celebrity performing and creative artists, was much photographed. But any reasonable viewer with access to a range of such photographs including the Goldsmith Photograph would have no difficulty identifying the latter as the source material for Warhol's Prince Series.

The Second Circuit ruled en banc that some issues of copyright infringement can, and should, at times be decided by the court, not the jury: "substantial similarity ... may be resolved as a matter of law where access to the copyrighted work is conceded, and the accused work is so substantially similar to the copyrighted work that reasonable jurors could not differ on this issue." The Supreme Court affirmed.

The Second Circuit's approach is also echoed by the Ninth Circuit's comments on jury instructions:

If the plaintiff shows that the defendant had access to the plaintiff's work and that there is a substantial similarity between the infringed and infringing works, a presumption of copying arises shifting the burden to the defendant to rebut the presumption or to show that the alleged infringing work was independently created.

The same conclusion about infringement in Warhol should have been applied in the Von D case.

The district court in the Von D case should have resolved a part of the case by directly handling the extrinsic portion of the substantial similarity test and possibly the intrinsic issue too, and then letting the jury decide the remaining issues.

The Appeal

Despite decades of litigation about the critical copyright term, "substantially similar," the courts have yet to provide a useful definition of the term that can apply to most cases.

On appeal, it is hoped that the Ninth Circuit will finally offer lower courts and litigants some meaningful guidelines on (1) who should decide whether protected elements in the copy are "substantially similar" to those in the original, and (2) provide useful, practical instructions as to how a jury or court should correctly apply the "substantial similarity" tests.

The court may also offer helpful guidance on jury instructions and verdict forms, as well as the proper role of the court when purposeful copying is apparent.

Suggestions for Practitioners

The plaintiff failed to provide the court with the level of detail about copying and substantial similarity to allow the court to consider the issue of infringement as a matter of law. While the plaintiff was correct to state that the photo and the tattoo are "remarkably similar," he did not explain why that was so and also did appreciate that the court would not bail him out for this deficiency.

The plaintiff should have offered a more detailed verdict sheet to provide instructions to the jury.

The suggestion that this case is a win for the entire tattoo industry is misplaced. Instead of relying on a potentially favorable court verdict, tattoo artists should expend some effort to determine if the proposed image for the tattoo is already copyrighted and, if so, seek a license or use a different image.

Such an approach, of course, is much cheaper than engaging in federal court litigation.

Finally, the copyright owner must be vigilant in removing from the internet copies of its images that are not marked with a copyright notice and should make sure that all copies have obvious copyright notices.

The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of their employer, its clients, or Portfolio Media Inc., or any of its or their respective affiliates. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice.